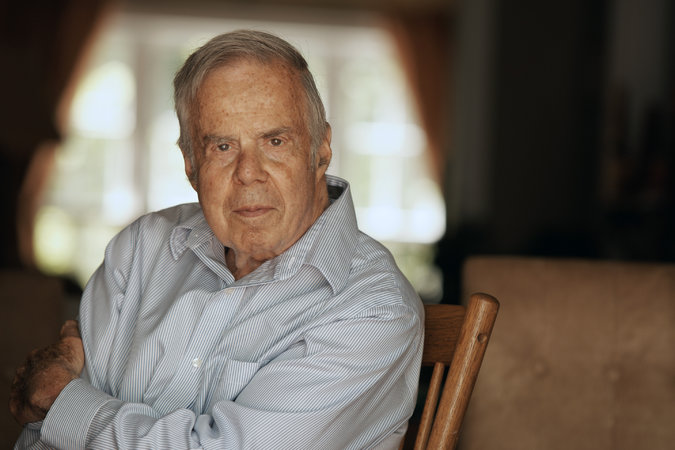

>> Robert Spitzer, Psychiatrist Who Set Rigorous Standards for Diagnosis, Dies at 83

[spacer]

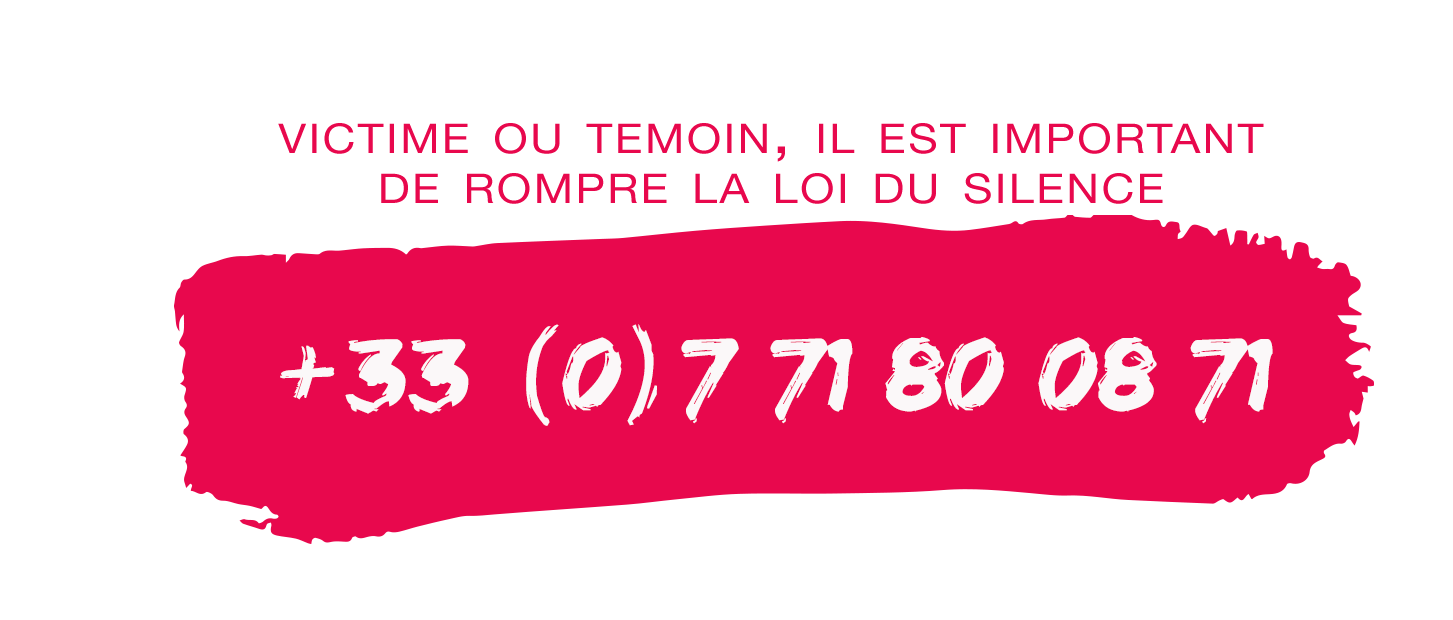

Le docteur Robert Sptizer, connu pour avoir établi une classification moderne des maladies mentales, est décédé ce vendredi à Seattle, à l’âge de 83 ans, indique europe1.fr. Selon sa femme, il aurait succombé à des problèmes cardiaques. Il avait notamment participé à la déclassification de l’homosexualité comme maladie mentale en 1973, après des négociations ardues.

Selon le docteur Allen Frances, interrogé par le New York Times, « Robert Spitzer était de loin le psychiatre le plus influent de son époque ». Il avait observé, puis retiré l’homosexualité de la liste des troubles mentaux, alors considérée par le DSM, manuel de diagnostic, comme un « dérangement sociopathique de la personnalité ».

« Un problème médical doit être associé soit à une détresse subjective, une douleur ou un souci de fonctionnement social », avait alors expliqué Robert Spitzer au Washington Post. Pour le docteur Jack Drescher, psychanalyste homosexuel, « si le « mariage gay » est aujourd’hui possible, c’est en partie grâce à lui ! »

En 2001, Robert Spitzer déclenchera pourtant une polémique en publiant une étude qui soutenait les thérapies de conversion, censées pouvoir transformer les homosexuels en hétérosexuels. Il s’était basé sur des témoignages de personnes qui, après avoir subies ces pratiques pseudo-scientifiques, affirmaient avoir changé. Mais, « comment évaluer la réorientation sexuelle d’un être humain ? ». Il s’est excusé en 2012, soulignant que cette étude était le « seul regret » de sa carrière ».

[spacer]

>> Dr. Robert Spitzer — a Jewish psychiatrist who played a leading role in establishing agreed-upon standards to describe mental disorders and eliminating homosexuality’s designation as a pathology — died Friday in Seattle. He was 83.

Dr. Spitzer’s work on several editions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or the DSM, defined all of the major disorders “so all in the profession could agree on what they were seeing,” said Williams, who worked with him on DSM-III, which was published in 1980 and became a best-selling book.

“That was a major breakthrough in the profession,” she said.

Spitzer came up with agreed-upon definitions of mental disorders by convening meetings of experts in each diagnostic category and taking notes on their observations, the New York Times reported.

“Rather than just appealing to authority, the authority of Freud, the appeal was: Are there studies? What evidence is there?” Spitzer told the New Yorker magazine in 2005. “The people I appointed had all made a commitment to be guided by data.”

Dr. Allen Frances, a professor emeritus of psychiatry at Duke University and editor of a later edition of the manual, told the Times that Spitzer “was by far the most influential psychiatrist of his time.”

Gay-rights activists credit Dr. Spitzer with removing homosexuality from the list of mental disorders in the DSM in 1973. He decided to push for the change after he met with gay activists and determined that homosexuality could not be a disorder if gay people were comfortable with their sexuality.

At the time of the psychiatric profession’s debate over homosexuality, Dr. Spitzer told The Washington Post: “A medical disorder either had to be associated with subjective distress — pain — or general impairment in social function.”

Dr. Jack Drescher, a gay psychoanalyst in New York, told the Times that Spitzer’s successful push to remove homosexuality from the list of disorders was a major advance for gay rights. “The fact that gay marriage is allowed today is in part owed to Bob Spitzer,” he said.

In 2012, Dr. Spitzer publicly apologized for a 2001 study that found so-called reparative therapy on gay people can turn them straight if they really want to do so. He told the Times in 2012 that he concluded the study was flawed because it simply asked people who had gone through reparative therapy if they had changed their sexual orientation.

“As I read these commentaries (about the study,) I knew this was a problem, a big problem, and one I couldn’t answer,” Dr. Spitzer told the Times. “How do you know someone has really changed?” Dr. Spitzer publicly apologized for that study in 2012, calling it the only thing in his career that he regretted.