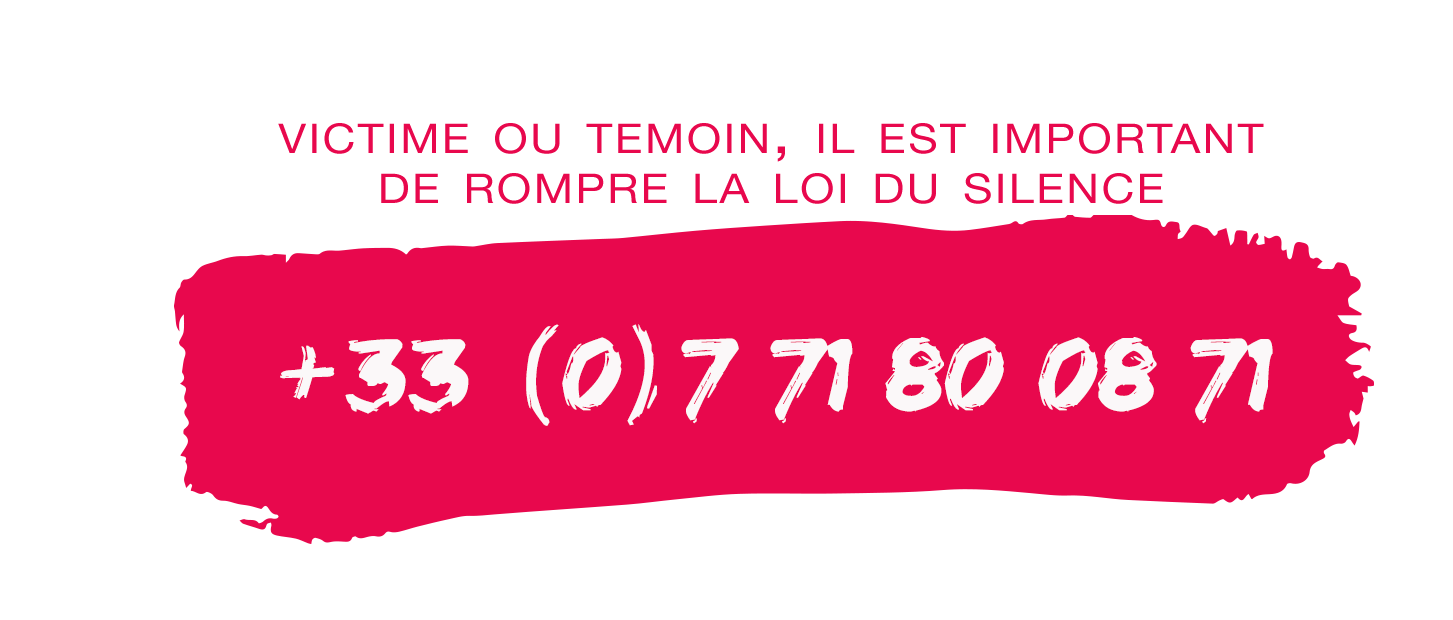

>> Robert De Niro: Me & My Gay Dad. Remembering The Artist Robert De Niro Sr. (HBO Documentary Films)

Ce n’est pas de lui dont il est question mais de son père, peintre méconnu, homosexuel, décédé en 1993, emporté par un cancer. L’icône du cinéma new-yorkais veut réhabiliter l’oeuvre paternelle dans ce documentaire signé Perri Peltz, et montrer, d’abord à ses enfants, qui était leur grand-père.

Remembering the Artist… a été dévoilé en avant-première au festival de Sundance en janvier. Il sera diffusé le 9 juin sur HBO. Robert de Niro en parle longuement cette semaine dans Out, le plus important magazine LGBT américain, qui décrit le film comme « le portrait d’un fils qui veut faire vivre l’héritage de son père ». Durant l’interview, l’acteur fond en larmes.

Robert de Niro, Sr. vivait mal d’être d’un artiste sans le sou et vivait mal son homosexualité : « Oui, probablement. Etant de cette génération, d’une petite ville, explique l’acteur de 70 ans. Je n’en étais pas trop conscient. J’aurais aimé qu’on en parle un peu plus. Ma mère ne parlait pas des choses en général, et à un certain âge, cela ne vous intéresse pas non plus. Encore une fois, c’est pour mes enfants, je veux qu’ils prennent le temps de réaliser qu’il ne faut pas attendre 20 ans pour faire les choses. » Dans le documentaire, Robert de Niro, les larmes aux yeux, lit de nombreux passages du journal intime de son père, où il exprime ses tourments amoureux.

En 1943, trois ans après la naissance du futur complice de Martin Scorsese, ses parents se séparent. Robert de Niro comprendra bien plus tard que c’est l’homosexualité de son père qui l’a poussé à quitter sa mère, la peintre et poétesse Virginia Holton Admiral. Malgré la séparation, ils restent proches : « Comme vous pouvez l’imaginer, nous n’étions pas le genre de père et de fils à jouer au baseball ensemble, mais nous avions une connexion. Je ne le voyais pas souvent à cause du divorce. Comme je le dis dans le documentaire, d’une certaine manière, je prenais soin de lui. Quand je pense à lui, je pense à mes enfants. J’essaye de communiquer avec eux, mais ce n’est pas facile. On en rigole. Ils ont leurs propres problèmes d’ado. Je leur donne de l’espace, mais quand je dois être là et être ferme, je le suis. Mon père n’était pas un mauvais père, ou un père absent… Il l’était en quelque sorte, absent, mais il était très aimant. Il m’adorait… comme j’adore mes enfants. »

Robet de Niro a donc entrepris ce documentaire avant tout pour ses six enfants et quatre petits-enfants. « J’ai senti que je devais le faire, confie-t-il à Out. Il était de ma responsabilité de faire ce film. J’ai toujours eu envie de le faire et puis mon associée m’a dit que c’était le bon moment. Ce n’était pas prévu de finir sur HBO. Mon idée originale a toujours été de le faire pour mes enfants. » Il y a le film… et le dernier atelier de Robert de Niro, Sr. Dans le quartier de SoHo à New York. Il y a quelques années, l’acteur a entrepris de tout archiver, tout photographier, tout filmer avant de se séparer des lieux : « Et puis je n’ai pas pu… »

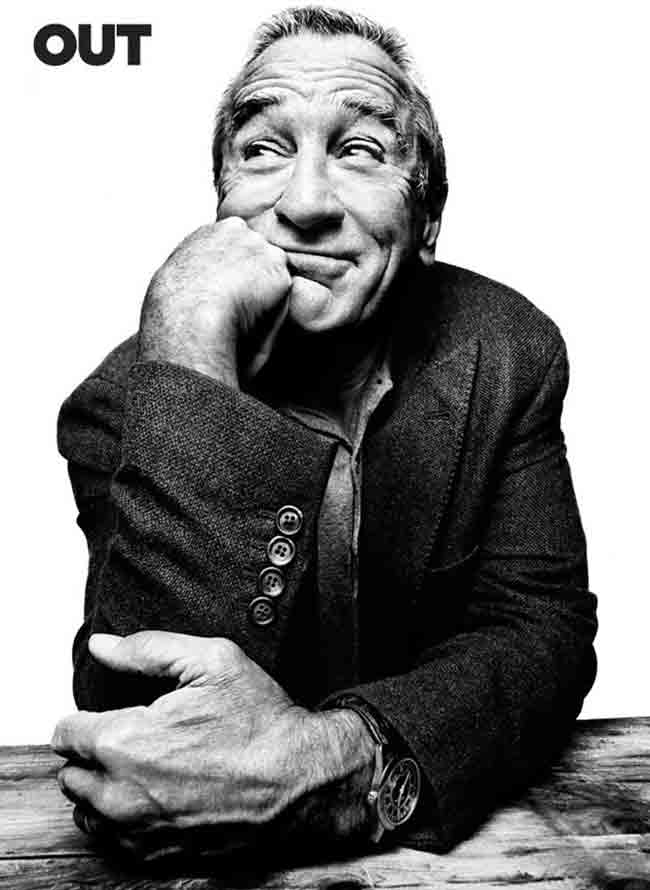

>> The legendary actor shares the story of his father, an artist who struggled for recognition as the city changed around him

Photography by Platon

Many of us think we know Robert De Niro. We know him as Travis Bickle or Vito Corleone or any number of other gangsters or bad guys. His ability to combine corrupted virtue with deep sorrow and wit — along with a fearsome sensuality — has made him a film hero with a tough exterior. Perhaps that’s why it’s so shocking to see him shake and sob as he talks about his late father, who lived openly as a gay man.

It’s been more than 20 years since Robert De Niro Sr.’s death from cancer, but his memory is fresh for his son, who has preserved his father’s final home and studio in New York City’s SoHo. Filled with books, paintbrushes, and hundreds of canvases, some of which he never finished, it looks like pop stepped away for a coffee and should be back to finish another still life before dinner. The loft remains a quiet shrine to an artist that few recognize, perhaps mistaking his figurative paintings for a late Matisse or another French master. “It was the only way to keep his being, his existence alive,” De Niro explains. “To me, he was always a great artist.”

Now 70, the actor has decided to reveal this hidden sanctum and his own struggle with his late father’s memory in a new documentary that premieres June 9 on HBO. In Remembering the Artist: Robert De Niro, Sr., directed by Perri Peltz, the son tears up as he reads from his father’s diaries. He shares intimate stories of his father’s despair about his sexual orientation and his stagnant artistic reputation. At one point, as De Niro was ascending to Hollywood’s top tier, he made a last-ditch effort to rescue his father, who was sick in Paris, where he’d been living as a starving artist. It’s clear that De Niro regrets that he wasn’t able to help him more before he died, and the film becomes a moving portrait of a son who wants to resurrect his father’s legacy before it’s too late. Out was given a rare glimpse into the legendary actor’s personal life, spending a day in his father’s studio. De Niro revealed a fragile, tender side as he explained why he hopes his dad’s work will live on.

After seeing the studio in the documentary, I wondered what this space meant to you. Do many people visit?

I’ve brought people here over the years. I’ve had a reception or two here. When I thought I was going to have to let it go, three or four years ago, I videotaped it and had photos taken and documented everything. But then I said, “I just can’t do it.”

It’s a different experience when you’re here than when you see it in photos. I did it for the grandkids and my young kids, who didn’t know their grandfather.

It amazes me that SoHo has these hidden spaces that, no matter what, never seem to change.

Exactly. And I like things that don’t change. I like consistency. Constancy. People look forward to tradition, they come back, it’s still there, nothing’s changed. Like when you go to a certain restaurant and you go back, and all of sudden it’s changed because they hired a new chef. If it’s not broke, don’t fix it. This space is here, and in 20 years, people won’t know what a real space like this will be unless it was in a museum and they recreated it.

After your father’s death, did you lock the door and not come back? Or did you take a while before you decided what to do with it?

I didn’t think of just selling it and dismantling it. Luckily, I could afford to keep it going, so I left it as is. My mother was alive then. I don’t remember what we discussed. I documented and went through everything to make sure we catalogued it, and then I said, “I’m keeping it like this.”

His older studios, like, a block away, maybe 60 years ago, were not like this. Then it was Siberia — for real — on West Broadway or LaGuardia Place. My mother had this place first and then she gave it to my father; they were friends. She came down here a long time ago. She had a place in the Meatpacking District, like, 50 years ago.

When did you begin to read his diaries?

I haven’t even read all the diaries — I started. I read the ones for the film, but I haven’t read all the other material. I will, of course.

One of the things that was very moving for me in the film was the fact that you’re named after your father. How do you feel about that — sharing a name — and when you become more famous than the person you’re named after?

[De Niro begins to cry, takes off his glasses, and pauses to collect himself.]

I get emotional. I don’t know why.

When you were younger, it sounded like you had problems connecting with each other.

We were not the type of father and son who played baseball together, as you can surmise. But we had a connection. I wasn’t with him a lot, because my mother and he were separated and divorced. As I say in the documentary, I looked after him in certain ways.

In what ways?

I think of my own kids. I try to communicate with them, but it’s hard. I joke about it with them. They have their issues as teenagers. I give them their space, but when I have to step in and be firm about something, I am. But my father wasn’t a bad father, or absent. He was absent in some ways. He was very loving. He adored me… as I do my kids.