>> The Scientific Quest to Prove Bisexuality Exists

Contributeur du New York Times, Benoit Denizet-Lewis a écrit dans le journal un long article sur les preuves scientifiques de la bisexualité. Pour y parvenir, il s’est entretenu avec plusieurs expert.e.s à ce sujet, notamment John Sylla et Denise Penn de l’Institut américain de la bisexualité (AIB). Pour Brad S. Kane, un membre gay du conseil d’administration de l’Institut, il est important de contribuer à faire reconnaître la bisexualité comme une orientation sexuelle à part entière: «Les personnes bisexuelles sont incomprises. On les ignore. On se moque d’elles. Même au sein de la communauté homo, je ne peux pas compter le nombre de gens qui m’ont dit: “Oh, je ne sortirais jamais avec un.e bi.e” ou “Les bi.e.s, ça n’existe pas”. Les gens pensent, et particulièrement les gays, que les hommes qui disent être bisexuels mentent, ou sont sur le point de devenir gays, ou sont juste inconstants et incapables de faire un choix.»

«VOS PUPILLES INDIQUENT QUE VOUS ÊTES PLUS BI QUE GAY»

Une fois posé ce constat, l’auteur de l’article livre plusieurs données sur l’invisibilité des bi.e.s. D’après une étude du Pew Research Center réalisée en 2013, 72% des bisexuel.le.s dissimulent leur orientation sexuelle. Le Williams Institute a quant à lui estimé que 3,1% des Américain.e.s sont bisexuel.le.s, alors que 2,5% sont lesbiennes ou gays.

En mai 2013, l’auteur de l’article du New York Times a pris part à une étude mettant en lien bisexualité et curiosité sexuelle, le présupposé étant que les bi.e.s sont sexuellement plus curieux/ses que les autres. Cette étude a été menée sur 60 hommes qui s’identifient comme étant gays. En mesurant la dilatation des pupilles de ces hommes à qui l’on présente des scènes de sexe incluant des hommes et des femmes, on parviendrait à déterminer leur véritable orientation sexuelle. «Vos pupilles se sont dilatées deux fois plus que la moyenne des hommes gays et autant qu’un homme hétérosexuel devant des femmes, a-t-on indiqué au journaliste qui se définit comme gay. Vos pupilles indiquent que vous êtes plus bi que gay.»

Benoit Denizet-Lewis a pris la nouvelle comme un choc car cela remettait profondément en question qui il est. Et il a finalement considéré qu’il était le seul à pouvoir déterminer sa propre identité: «Je ne crois pas être bisexuel, peu importe ce qu’en disent mes pupilles. Ce n’est pas ma véritable orientation sexuelle et ça ne correspond pas à mon identité. Bien que je ne méprise pas la valeur d’une étude en laboratoire sur l’excitation, j’ai parlé à plusieurs militant.e.s bi.e.s qui méprisent ces tests. La sexualité, m’ont-ils/elles dit, est bien trop complexe pour être quantifiée grâce à nos réactions devant de la pornographie.»

POURQUOI N’EST-ON SCEPTIQUE QU’ENVERS LES BI.E.S?

La façon dont Benoit Denizet-Lewis invalide cette étude pour lui-même, tout en considérant qu’elle est valable pour d’autres, est un des reproches que lui adresse Rachel, une contributrice du magazine en ligne AutoStraddle. Elle relève que les études sur l’authenticité de la bisexualité ont beau être financées par des organismes comme l’AIB, elles ne sont pas réalisées par des bi.e.s et encore moins sur des bi.e.s, l’étude mesurant la dilatation des pupilles ne concernant que des hommes gays.

«On permet aux hétéros et aux homos de s’identifier comme tel.le.s en dehors de toute expérience sexuelle, rappelle-t-elle. On présume que les hétéros sont hétéros avant même d’avoir eu une expérience sexuelle, et les homos sont d’ordinaire (même si ce n’est pas toujours le cas) cru.e.s par les autres lors de leur coming-out, même lorsqu’ils/elles n’ont pas eu de relation sexuelle avec une personne du même sexe. Alors pourquoi les chercheurs/ses restent sceptiques lorsqu’il s’agit de la bisexualité d’une personne quand celle-ci s’identifie comme étant bisexuel.le, quand elle a eu des relations avec des personnes de plusieurs genres, quand elle a peut-être dû affronter la désapprobation des hétéros comme des homos mais qu’elle a malgré tout continué à s’identifier comme bie, à moins qu’ils/elles ne soient parvenu.e.s à mesurer la dilatation de ses pupilles à la vue de parties génitales? Beaucoup de personnes dans cet article semblent prendre au mot les hétéros et les homos, mais quand il s’agit des bisexuel.le.s, on reste coincé à ce qu’elles appellent “l’épineux problème de l’identité face au comportement”.»

Elle pointe également du doigt le fait que très peu de femmes prennent la parole dans l’article du New York Times. «Les hommes bisexuels et leurs expériences sont les plus mises en avant, ce qui donne l’impression fausse que a) les problèmes des hommes bisexuels sont les plus importants, et b) que les problèmes des hommes bisexuels sont les problèmes de tou.te.s les bisexuel.le.s. De la même façon que les gays et les lesbiennes font face à des problèmes et des oppressions différents – les lesbiennes ne sont généralement pas perçues comme un accessoire pour les femmes hétéros qui adorent faire du shopping, et des inconnu.e.s ne demandent pas aux gays comment ils font pour avoir des relations sexuelles avec pénétration – les bi.e.s des différents genres font face à des problèmes très différents.»

LA VIE DES BI.E.S N’EST PAS PLUS FACILE

Tout n’est pas à jeter dans l’article du New York Times, loin s’en faut. Benoit Denizet-Lewis rappelle, faits à l’appui, le poids de la communauté homosexuelle dans l’invisibilisation des personnes bies. Lorsque le plongeur Tom Daley a fait son coming-out de bi, l’écrivain gay Andrew Sullivan a insinué que le jeune homme était dans une phase de transition. Des décennies plus tôt, les homos exprimaient même ouvertement de la défiance à l’encontre des bi.e.s: la Société pour les droits humains, inspirée par le docteur gay allemand Magnus Hirschfeld et fondée à Chicago en 1924, rassemblait des gays mais a tenté d’exclure les bi.e.s. Pendant les années 90, les hommes bis ont été accusés de transmettre le sida aux femmes.

Quand la militante bisexuelle Robyn Ochs a fait son coming-out à l’université auprès de lesbiennes, elle a été rejetée, raconte-t-elle dans le New York Times: «Elles m’ont dit qu’on ne pouvait pas me faire confiance, que les bies quittent toujours leurs compagnes pour un homme. Si j’avais fait mon coming-out en tant que lesbienne, j’aurais été accueillie à bras ouverts, on m’aurait invitée aux fêtes, j’aurais pu rejoindre l’équipe de softball. Le tapis rouge des lesbiennes, si vous voulez. Mais dire que je suis lesbienne signifiait que j’aurais dû renier l’attrait que j’avais pu ressentir pour les hommes comme si je n’étais pas vraiment consciente.»

C’est l’un des rares témoignages de femmes dans l’article du New York Times. Pour Rachel d’AutoStraddle, Benoit Denizet-Lewis s’est contenté d’opposer deux groupes de femmes, sans mentionner d’autres sujets importants, comme le fait que presque la moitié des femmes bisexuelles ont été violées. L’auteur de l’article du New York Times cite toutefois Brian Dodge, chercheur à l’Université de l’Indiana, qui a démontré que les dépressions, l’anxiété, l’usage de drogues, les comportements suicidaires et les problèmes de santé sexuelle sont plus répandus chez les bi.e.s que chez les hétéros et les homos. «En gros, il n’est pas simple d’être bisexuel.le», indique-t-il, détruisant un préjugé largement répandu.

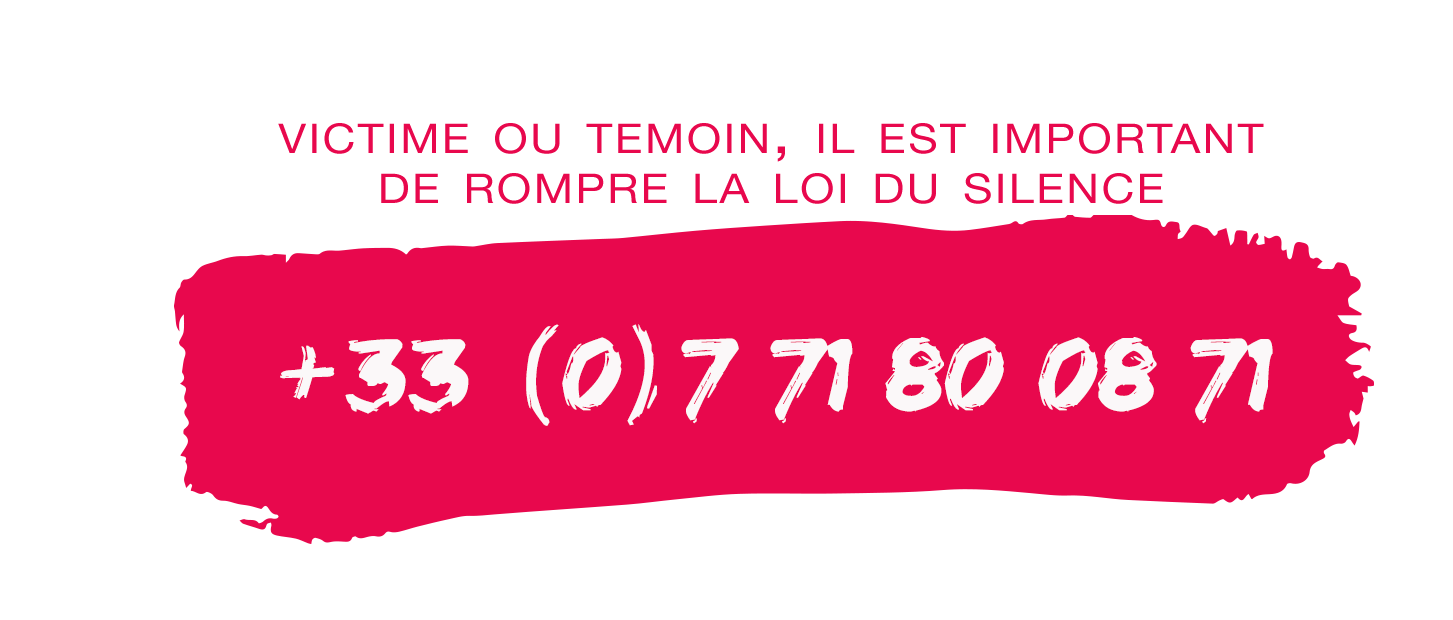

En France, les préoccupations liées à la biphobie ont fait l’objet d’une enquête menée l’an dernier par SOS homophobie, avec Act Up Paris, Le Mag et Bi’Cause.

>> Traduction de l’article du New York Times :

Benoit Denizet-Lewis, a contributing writer for the magazine, wrote this week’s cover story about using science to prove that bisexuality exists.

The traffic was bad, even by the warped standards of a Southern California commute. We were headed south from Los Angeles to San Diego on an overcast morning last spring, but we hadn’t moved in 10 minutes.

I was sandwiched in the back seat of the car between John Sylla and Denise Penn, two board members of the Los Angeles-based American Institute of Bisexuality (A.I.B.), a deep-pocketed group partly responsible for a surge of academic and scientific research across the country about bisexuality. We were on our way to an A.I.B. board meeting, where members would decide which studies to fund and also brainstorm ways to increase bisexual visibility “in a world that still isn’t convinced that bisexuality — particularly male bisexuality — exists,” as Allen Rosenthal, a sex researcher at Northwestern University, told me.

When someone suggested that we try another route, Sylla, A.I.B.’s friendly and unassuming 55-year-old president, opened the maps app on his iPhone. I met Sylla the previous day at A.I.B. headquarters, a modest two-room office on the first floor of a quiet courtyard in West Hollywood that’s also home to film-production companies and a therapist’s office. Tall and pale, with an easy smile, Sylla offered me books from A.I.B.’s bisexual-themed bookshelf and marveled at the unlikelihood of his bisexual activism. “For the longest time, I didn’t even realize I was bi,” Sylla said. “When I did, I assumed I’d probably just live a supposedly straight life in the suburbs somewhere.”

Continue reading the main story

‘To come out as bisexual now would be like starting over in some way. My mom and dad would fall over. It was hard enough to convince them that I was gay.’

In the back seat, Sylla lifted his eyes from his phone and suggested an alternate course. Then he shrugged his shoulders. “We could go either way, really,” he told us. He smiled at me. “Get it? Either way?”

“This is what happens when you’re stuck in a car with bisexual activists,” said Brad S. Kane, who was behind the wheel. “More bisexual-themed puns and plays on words than any human should have to endure.”

A lawyer in his late 40s, Kane likes to call himself A.I.B.’s “token gay board member.” Though he had a relationship with a woman almost 20 years ago (and recently met a “French actress and rocker” to whom he was attracted), he’s primarily interested in men. “Everyone in A.I.B. seems to think I’m a closet bisexual,” he said, “but there are a host of emotional reasons why I choose to identify as gay. For one thing, it simplifies my life. To come out as bisexual now would be like starting over in some way. My mom and dad would fall over. It was hard enough to convince them that I was gay.”

I asked him why a man who identifies as gay was involved with A.I.B.

“Let me tell you a story,” he said, recalling the time he represented a heterosexual woman in a case against gay neighbors who were trying to have her dog put down. “People would say, ‘You’re gay — why aren’t you helping the gay couple?’ I’d say, ‘Because I always side with the underdog.’ The poor dog was in animal prison at animal control, with nobody to advocate for it. The dog needed help, needed a voice.” He paused and caught my eye in the rearview mirror. “You’re probably wondering where this is going and whether I’ll shut up anytime soon.”

“I know I am,” said Ian Lawrence, a slender and youthful 40-year-old A.I.B. board member in the passenger seat.

Continue reading the main story

“Well, bisexual people are kind of like that dog,” Kane said. “They’re misunderstood. They’re ignored. They’re mocked. Even within the gay community, I can’t tell you how many people have told me, ‘Oh, I wouldn’t date a bisexual.’ Or, ‘Bisexuals aren’t real.’ There’s this idea, especially among gay men, that guys who say they’re bisexual are lying, on their way to being gay, or just kind of unserious and unfocused.”

Lawrence, who struggled in college to understand and accept his bisexuality, nodded and recalled a date he went on with a gay television personality. When Lawrence said that he was bisexual, the man looked at him with a pained face and muttered: “Oh, I wish you’d told me that before. I thought this was a real date.”

Hoping to offer bisexuals a supportive community in 2010, Lawrence became the head organizer for amBi, a bisexual social group in Los Angeles. “All kinds of people show up to our events,” he told me. “There are older bi folks, kids who say they ‘don’t need any labels,’ transgender people — because many trans people also identify as bi. At our events, people can be themselves. They can be out.”

“Though most bisexuals don’t come out,” Sylla said. “Most bisexuals are in convenient opposite-sex relationships and aren’t open about their sexual orientation. Why would you be open, when there is so much biphobia?”

Spend any time hanging around bisexual activists, and you’ll hear a great deal about biphobia. You’ll also hear about bi erasure, the idea that bisexuality is systematically minimized and dismissed. This is especially vexing to bisexual activists, who point to a 2011 report by the Williams Institute — a policy center specializing in L.G.B.T. demographics — that reviewed 11 surveys and found that “among adults who identify as L.G.B., bisexuals comprise a slight majority.” In one of the larger surveys reviewed by the institute (a 2009 study published in The Journal of Sexual Medicine), 3.1 percent of American adults identified as bisexual, while 2.5 percent identified as gay or lesbian. (In most surveys, the institute found that women were “substantially more likely than men to identify as bisexual.”)

Then there’s the tricky matter of identity versus behavior. Joe Kort, a Michigan-based sex therapist whose next book is about straight-identified men who are married but who also have sex with men, says that “many never tell anyone about their bisexual experiences, for fear of losing relationships or having their reputation hurt. Consequently, they’re an invisible group of men. We know very little about them.”

Bisexuals are so unlikely to be out about their orientation — in a 2013 Pew Research Survey, only 28 percent of people who identified as bisexual said they were open about it — that the San Francisco Human Rights Commission recently called them “an invisible majority” in need of resources and support.

But in the eyes of many Americans, bisexuality — despite occasional and exaggerated media reports of its chicness — remains a bewildering and potentially invented orientation favored by men in denial about their homosexuality and by women who will inevitably settle down with men. Studies have found that straight-identified people have more negative attitudes about bisexuals (especially bisexual men) than they do about gays and lesbians, but A.I.B.’s board members insist that some of the worst discrimination and minimization comes from the gay community… (read more : http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/23/magazine/the-scientific-quest-to-prove-bisexuality-exists.html?_r=0)

>> Interview :

What interested you in doing a story about bisexuality?

My first cover story for the magazine, back in 2003, was about men on the down low, some of whom identified as bisexual — and many of whom engaged in bisexual behavior. I’ve spent a good part of my adult life writing and thinking about sexuality, gender and identity, and about the complicated ways we project or hide our identities. When I learned about the American Institute of Bisexuality (A.I.B.) and the increase in research happening right now because of the group’s funding, I knew I wanted to explore what A.I.B. hoped to achieve — and what the new research was telling us about an orientation that, remarkably, many people still dismiss.

Were you surprised by how much so-called biphobia is experienced by bisexuals?

I was really surprised by how misunderstood and dismissed many bisexual people feel, and the research backs that up. Most bisexuals say they aren’t open to people in their lives about their orientation. And, really, there is little upside to being open about it. If you’re a bisexual man married to a woman and living in the suburbs somewhere, you’re not going to correct your neighbors over dinner when they assume you’re heterosexual. There’s very little reason to do that. I also spoke to some men who live outwardly “gay” lives and keep their bisexuality quiet, because they’ve learned that if they share the true complexity of their orientation in a group of gay men, someone will invariably dismiss them by saying something like: “Oh, honey, we were all bisexual for a minute. You’ll grow out of that.”

Is there a generational divide between older and younger bisexuals? Did the college students you talked to seem to have less trouble making their way?

Yes, younger bisexuals are more likely to be out. Colleges and universities are some of the safest places to be bisexual, or to be trying to figure that all out. The word “bisexual” still can have a negative connotation, though, and many students are looking for new ways to say basically the same thing — that they’re not concerned with gender when it comes to their romantic and sexual attractions.

I attended a event at the College of Wooster in Ohio where we were handed a sheet of paper outlining and defining some of the alternatives to the word bisexual, including pansexual (“attracted to a person without regards for gender”), anthrosexual (“another word for pansexual”), omnisexual (“characterized by a diverse number of sexual orientations”) and something called bar-sexual (“a slang term to refer to peoples that will only experiment with same-gender attraction while in a specific situation, usually involving alcohol”). I initially thought that last one was a joke, but the panel moderators spoke about it very seriously.

Was anyone critical of the American Institute of Bisexuality?

I heard one or two rumblings of dissatisfaction with A.I.B., but it was mostly about the focus of the research A.I.B. helps to fund. Many bisexual activists would prefer that money go to studies that will help solve health disparities that bisexual people face, rather than another study looking at arousal in a lab setting.

Do you know any more about Fritz Klein, the man who founded the institute?

It’s unfortunate that I didn’t have the space to include more about Fritz Klein. He was a fascinating man who developed the Klein Sexual Orientation Grid, which measures sexual orientation through seven dimensions or vectors: sexual attraction, sexual behavior, sexual fantasies, emotional preferences, social preference, self-identification and lifestyle. Because Klein believed that sexuality could change over time, users responded to each dimension in terms of their past, present and ideal. (Klein identified as “bi-gay,” meaning he was closer to the homosexual end of the spectrum.)

Considering that you got split results from eye tests versus arousal tests, do you think that the science is prone to error, or that the difference between gay and bisexual is less clear than we might think?

That’s a great question, and I don’t really know the answer. To me, these kinds of tests have numerous potential drawbacks. For one thing, some people simply don’t get aroused in a lab setting. I was surprised, frankly, that I did. (Before going into the lab at Northwestern, I’d told the researcher that “you can’t just show me a video of any two guys having sex and expect me to be aroused,” especially in a lab with something attached to my privates.)

The larger problem, though, seems to be how to interpret the data. The Northwestern researchers were interested in studying “aversion” as it relates to bisexuality. Basically, they theorized that some men who are primarily attracted to men might consider themselves bisexual because they’re not “averse” to women. To test that, the researchers showed these guys a scene involving two men, and then a scene with two men and a woman. I was surprised that they didn’t seem concerned by the possibility that some of the gay-identified men might have their “aversion” complicated by the fact that they’re attracted to heterosexual men. Some gay men prefer heterosexual porn, not because they’re turned on by women, but because they’re turned on by “straight” guys. I wondered how the study of twosomes and threesomes could control for that factor, or others I hadn’t even considered.

I interviewed some of the people photographed for this story, and a few repeated what the longtime bisexual activist Mike Szymanski said: that their parents thought being bisexual meant a choice, and so they wished their child would pick the easy path. As you write, this is a problematic line of reasoning. Did most people you talked to feel that bisexuality was a choice?

No. Though they certainly have a choice in the gender of the person that they end up with, they don’t have a “choice” in who they are attracted to — just like straight and gay people don’t make a conscious decision about that. Many bisexuals have to laugh, though, at the idea that being bisexual allows them better chances at getting laid or finding a relationship. Szymanksi may have said it best: “Rodney Dangerfield is credited with saying it doubles your chances of having a date. I always thought that it halved your chances, because whether you told straight or gay people that you were bi, they both ran.”