>> Bishop of Grantham first C of E bishop to declare he is in gay relationship

[spacer]

Mgr Nicholas Chamberlain, évêque de Grantham, ville natale de Margaret Thatcher, dans l’est de l’Angleterre, est devenu le premier de la puissante Eglise anglicane d’Angleterre à faire son coming out et révéler, dans la foulée d’une interview publiée ce vendredi 2 septembre dans le Guardian, qu’il entretenait « une relation sérieuse avec son partenaire ».

Selon le quotidien britannique, des rumeurs sur l’homosexualité de certains évêques « circulent depuis des décennies », mais aucun ecclésiastique n’avait jusqu’ici abordé ouvertement le propos.

Ruth Hunt, responsable de l’organisation de défense des droits des personnels LGBT Stonewall, a salué sur Twitter un acte d’un « incroyable courage ».

Une décision contrainte, face aux menaces d’« outing » d’un journal dominical, dont il ne citera pas le nom, avoue néanmoins Mgr Chamberlain, qui regrette d’avoir eu à s’exprimer sur son orientation sexuelle en place publique : « Les gens savent que je suis gay (…). J’ai une sexualité, cela fait partie de moi, mais c’est sur mon ministère que je veux me concentrer. »

Justin Welby, l’archevêque de Canterbury et primat de la Communion anglicane, qui regroupe quelque 85 millions de croyants dans le monde, a reconnu être au courant « de la relation dans laquelle l’évêque est engagé depuis longtemps ». Mais il insiste, sa consécration en novembre dernier a été décidée « sur la base de ses qualités et de sa capacité à servir l’Eglise » et non pas sa sexualité, « sans rapport avec ses fonctions ».

En outre, « il serait injuste d’exclure de l’accès à l’épiscopat toute personne cherchant à vivre pleinement en conformité avec l’enseignement de l’Église sur l’éthique sexuelle ou sur d’autres domaines de la vie personnelle ou de la discipline », rappelle également l’institution dans un communiqué adressé aux paroissiens.

« Nous ne doutons pas qu’il a de nombreux dons comme pasteur », a réagi de son côté la Conférence globale sur l’avenir de l’anglicanisme (Gafcon), recouvrant l’aile conservatrice de l’Église, qui estime cependant que « certains aspects de la nomination de Nicholas Chamberlain sont une cause sérieuse de préoccupation pour les Anglicans bibliquement orthodoxes », et donc « une erreur majeure ».

Si elle affirme son attachement à « la compréhension traditionnelle de l’institution du mariage comme étant entre un homme et une femme », l’Eglise d’Angleterre autorise depuis 2005 les hommes et femmes homosexuels « unis dans le cadre d’un partenariat civil » à devenir prêtres, et être ordonnés en tant qu’évêques depuis 2013. Mais « à condition de rester chastes ». En revanche, les hétérosexuels mariés ne sont pas soumis à cette règle de l’abstinence.

Une « reconnaissance » qui continue toutefois d’exacerber les tensions entre les branches plus libérales, aux Etats-Unis notamment ou en Grande-Bretagne, aux conservateurs majoritaires au Kenya ou au Nigeria par exemple.

Mgr Chamberlain espère servir d’exemple, en tant que porte-parole de la communauté au sein du clergé, et s’il peut en encourager d’autres à se manifester, « ce sera super ! », conclut-il.

Joëlle Berthout

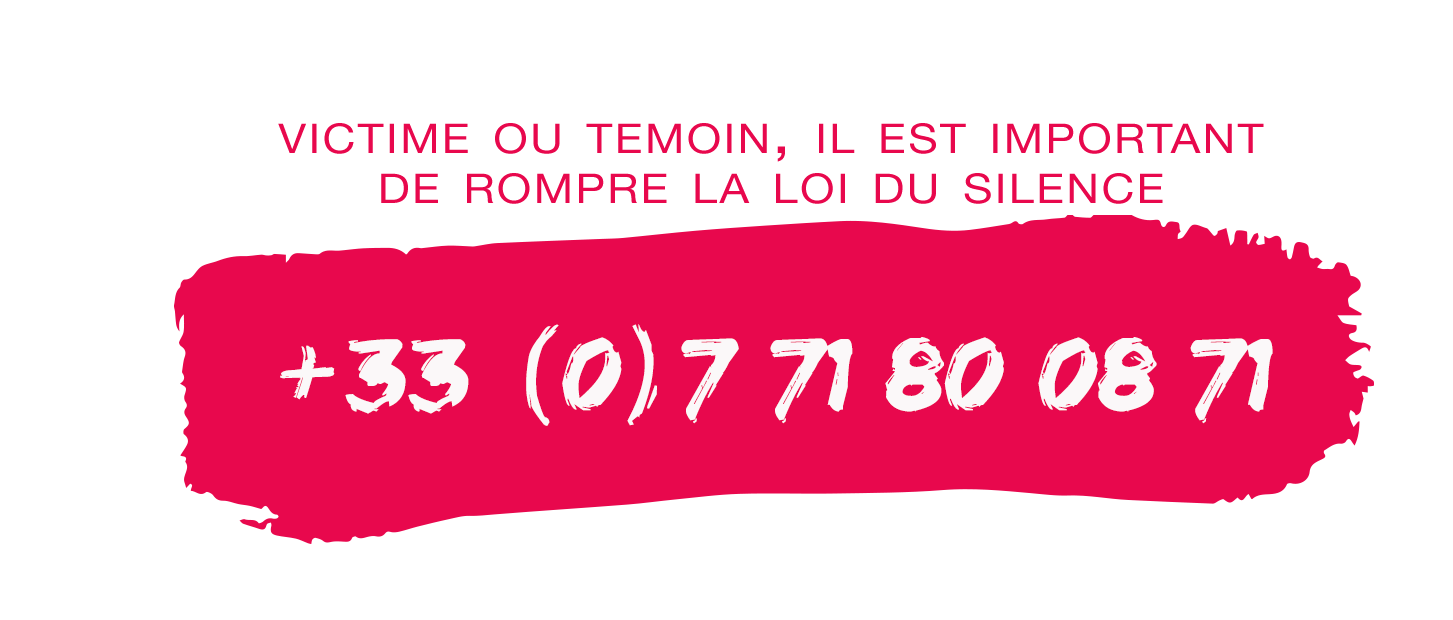

Stophomophobie.org

[spacer]

>> The bishop of Grantham has become the first Church of England bishop to publicly declare that he is gay and in a relationship.

In a move that will be embraced by campaigners for equality but is likely to alarm conservatives who fear the church is moving away from traditional teachings, Nicholas Chamberlain said there had been no secret about his long-term – albeit celibate – relationship with his partner.

But a threat by a Sunday newspaper to reveal Chamberlain’s sexuality had pushed him to speak publicly. He acknowledged that the revelation would cause « ripples » within the church. « It was not my decision to make a big thing about coming out, » he told the Guardian in an exclusive interview. « People know I’m gay, but it’s not the first thing I’d say to anyone. Sexuality is part of who I am, but it’s my ministry that I want to focus on.”

As bishop of Grantham becomes first openly gay C of E bishop, church’s official line does not fit reality among clergy

Chamberlain was consecrated last November, and all those involved in his appointment – including Justin Welby, the archbishop of Canterbury – were aware of his personal situation. During the process of being appointed as suffragan bishop of Grantham, he said, « I was myself. Those making the appointment knew about my sexual identity. » His appointment was made by the diocesan (senior) bishop of Lincoln, Christopher Lowson, and endorsed by Welby.

Chamberlain said he adhered to church guidelines, under which gay clergy must be celibate and are not permitted to marry. In the appointments process, « We explored what it would mean for me as a bishop to be living within those guidelines, » he said.

In a statement, Welby said: « I am and have been fully aware of Bishop Nick’s long-term, committed relationship. His appointment as bishop of Grantham was made on the basis of his skills and calling to serve the church in the diocese of Lincoln. He lives within the bishops’ guidelines and his sexuality is completely irrelevant to his office. »

In a letter to parishes in his diocese, Lowson said: « I am satisfied now, as I was at the time of his appointment, that Bishop Nicholas fully understands, and lives by, the House of Bishops’ guidance on issues in human sexuality. For me, and for those who assisted in his appointment, the fact that Bishop Nicholas is gay is not, and has never been, a determining factor. »

The C of E has been deeply divided over issues of sexuality. For the past two years, it has been involved in a series of painful internal discussions on the church’s attitudes to LGBT people and whether it can accept same-sex marriage. Its traditional belief that marriage is a union of a man and a woman has come under pressure from societal change and growing demands within the church that gay people should be accepted and allowed to marry in church.

An increasing number of priests have married or plan to marry same-sex partners in defiance of the ban on gay clergy marrying.

This week, a group of C of E conservative evangelical parishes held a meeting to discuss their response to what they claimed to be the watering-down of the authority of the Bible on the issue of sexuality, in what was billed as potentially the first step towards a breakaway from the Anglican church. It followed Welby’s recent comments at a Christian festival, when he said he was « constantly consumed with horror » at the church’s treatment of lesbians and gay men.

Chamberlain said he had been with his partner for many years. « It is faithful, loving, we are like-minded, we enjoy each other’s company and we share each other’s life, » he said.

Stressing that he did not want to become known as « the gay bishop », he said he hoped that the impact of his openness would be « that we can say the bishop of Grantham is gay and is getting on with his life and ministry ». However, as a member of the C of E’s College of Bishops, which meets this month to discuss the next stage of the church’s discussions about sexuality, Chamberlain may come under pressure to be a representative for LGBT rights.

« I will speak [at the meeting], and this part of me will be known. I hope I’ll be able to be a standard-bearer for all people as a gay man. And I really hope that I’ll be able to help us move on beyond matters of sexuality, » he said. « It’s not to say this isn’t an important matter – I’m not brushing it aside, » he added. But the church needed to focus on issues such as deprivation, inequality and refugees, he said.

Asked whether other bishops might follow his lead in openly declaring their sexuality, he said: « I really can only speak for myself. If I’m an encouragement to others, that would be great. »

Chamberlain said the C of E was “still at the beginning of a process of learning” about issues of sexuality, describing it as a struggle. « I don’t think we’ve reached a position where the church is going to be marrying same-sex couples, » he said. He declined to express objections to the C of E’s celibacy rule for gay clergy. “My observation of human beings over the years has shown me how much variety there is in the way people express their relationships. Physical expression is not for everyone. »

He hoped to be « judged by my actions as a parish priest, a bishop – and by the Lord ultimately. My sexual identity is part of who I am, but it’s the ministry that matters. »

In a statement, the C of E said: « The church has said for some time that it would be unjust to exclude from consideration for the episcopate anyone seeking to live fully in conformity with the church’s teaching on sexual ethics or other areas of personal life and discipline. »

Rumours about gay bishops have circulated for decades, but no serving bishop has ever before gone public about their sexuality. David Hope, the former archbishop of York, said that his sexuality was a « grey area » after being threatened with being « outed »; and former archbishop of Canterbury George Carey claimed to have knowingly consecrated two celibate gay men as bishops in the 1990s.

In 2003 the Times reported that the Right Rev Peter Wheatley, then the bishop of Edmonton, was gay and living with his partner. He said he was « a celibate Christian living by Christian teachings ».

Also in 2003, Jeffrey John, now the dean of St Albans, was nominated as bishop of Reading while being in a same-sex relationship with another C of E priest. Despite publicly declaring the relationship to be celibate, John withdrew from the nomination after an outcry from conservative Anglicans.

In the same year in the US, Gene Robinson was elected as bishop of New Hampshire, a move that split the Episcopal church. Earlier this year the US church was subject to de facto sanctions by the global Anglican Communion for embracing same-sex marriage.