>> Slovak vote on same-sex marriage alarms rights activists

Vidéos agressives, accusations d’«immoralité» et de «perversion»: la campagne pour le référendum censé barrer la route au mariage homosexuel, prévu samedi en Slovaquie, a réveillé des démons que l’on croyait morts et enterrés.

En fait, estime Guillaume Bonnet, directeur des campagnes du mouvement international pour l’égalité All Out interrogé à Paris, «il s’agit d’une vague du mouvement anti-gay qui refait surface en Europe, par exemple en Italie» et «reprend les mêmes arguments fallacieux que la Manif pour tous», mouvement qui a tenté d’empêcher l’acceptation du mariage homosexuel en France. À preuve, «la campagne contre le mariage homosexuel en Slovaquie a emprunté le logo de la Manif pour tous».

Dans une vidéo de l’Alliance pour la famille, mouvement à l’origine de la consultation, diffusée sur internet en Slovaquie, un garçon attend l’arrivée de ses parents adoptifs. Il est déçu quand il voit arriver deux hommes. «Où est Maman ?» demande-t-il.

Une autre vidéo, où l’on voit deux hommes caressant la tête d’un jeune garçon, ne révèle pas sa provenance et l’Alliance a démenti en être l’auteur. «Aimeriez-vous grandir dans une famille comme ça?» demande le garçon.

Alors que le référendum est a priori inutile – la Slovaquie n’autorise ni le mariage entre personnes de même sexe, ni même leur union civile – et sera probablement non valide faute d’atteindre le taux de participation de 50%, la campagne a révélé des réserves de haine à l’égard des homosexuels dans ce pays de l’UE de 5,4 millions d’habitants, dont plus de 80% se disent chrétiens et 70% catholiques.

L’été dernier, 400 000 signatures ont été rapidement recueillies pour demander la consultation.

À quelques jours du vote, un prêtre catholique de rite oriental a taxé en public les homosexuels d’«immoraux» et «pervers», appelant la société à combattre cette «plaie» et à repousser cette «saleté» hors des frontières nationales.

«Le but de ce référendum est de protéger la famille et les enfants», a déclaré à l’AFP le porte-parole de l’Alliance, Anton Chromik, dénonçant des lois votées par le Parlement européen et quelques pays membres de l’UE, qui «sapent la nature unique du mariage».

Les Slovaques sont invités à répondre à trois questions: sur le mariage entre personnes de même sexe, sur l’adoption d’enfants par des couples ou des groupes de même sexe, et sur le droit des parents de refuser que leurs enfants assistent à des cours sur la sexualité ou l’euthanasie.

Le refus du mariage homosexuel a été inscrit l’année dernière dans la Constitution slovaque par le parti social-démocrate du premier ministre Robert Fico, avec la définition du mariage comme «l’union exclusive entre un homme et une femme».

Le refus du mariage homosexuel a été inscrit l’année dernière dans la Constitution slovaque par le parti social-démocrate du premier ministre Robert Fico, avec la définition du mariage comme «l’union exclusive entre un homme et une femme».

Les principaux intéressés, discrets et peu revendicatifs, ont cherché à faire entendre leur voix.

«Nous continuerons à chercher la reconnaissance légale des couples de même sexe», dit Martin Macko, chef du groupe LGBT Initiative Inakost, relevant que des pays catholiques et conservateurs, telles l’Irlande et Malte, acceptent l’union civile entre homosexuels.

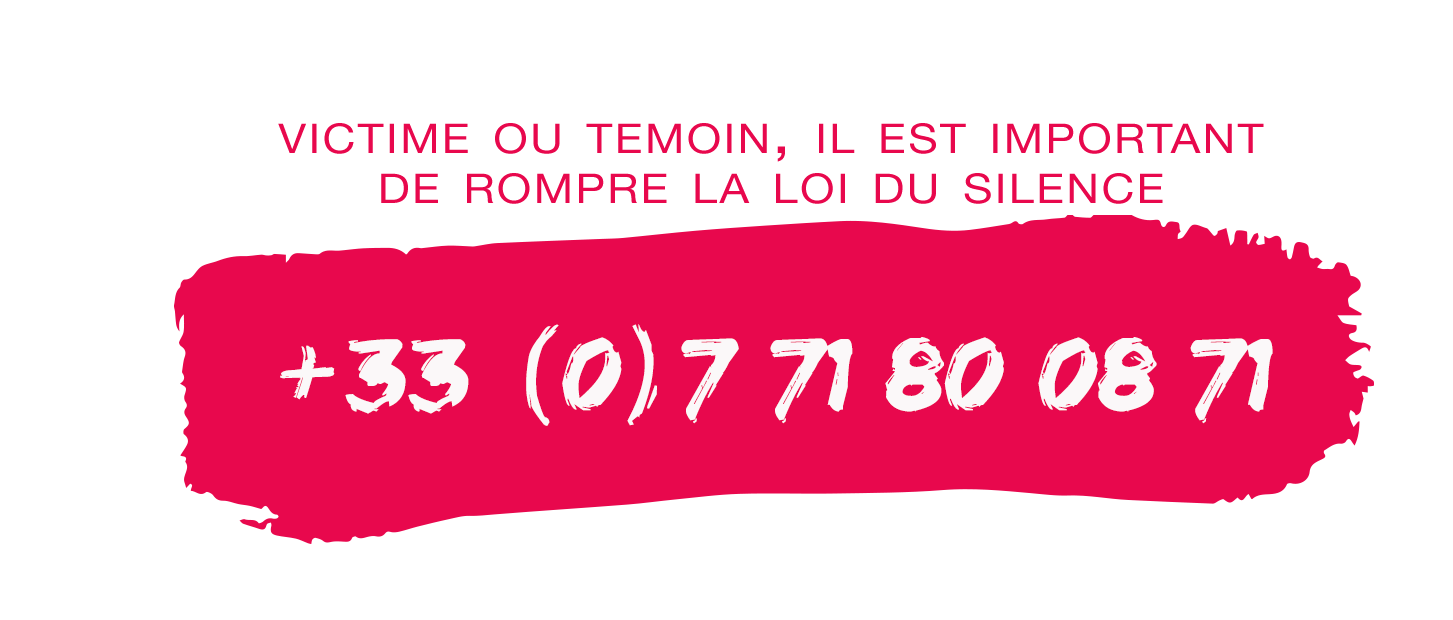

«Je n’irai pas voter et valider ce référendum avec ma voix», dit à l’AFP Andrea Pallang, propriétaire d’une galerie d’art à Bratislava, qui cohabite avec son amie depuis huit ans.«Je me sens victime de discrimination en matière d’impôts, de politique sociale et de services de santé», ajoute-t-elle.

Amnistie Internationale a mis en garde contre «un recul significatif de la Slovaquie» et une possible violation de la convention des Nations Unies sur la discrimination contre les femmes.

«Si le public répond oui à ces questions et cela est inscrit dans la loi, la Slovaquie renforcera la discrimination homophobe et sapera l’éducation sexuelle», a dit Barbora Cernusakova, chercheuse travaillant pour l’organisation humanitaire.

«La participation ne dépassera pas 35%», dit à l’AFP un analyste de l’hebdomadaire Trend, Marian Lesko. Sur les sept référendums précédents organisés depuis l’indépendance en 1993, un seul a été déclaré valide, celui concernant l’entrée dans l’UE.

>> Rights activists are sounding the alarm over a referendum in EU-member Slovakia on Saturday designed to cement a constitutional ban on gay marriage, pointing to a rise in hate speech.

Amnesty International earlier this week accused the conservative circles that have pushed the referendum of « pandering to homophobic discrimination ».

It added, in a statement, that any blanket ban on same-sex adoption would violate international human rights standards and the United Nations convention on discrimination against women.

« It’s part of a resurgent wave of anti-gay movements in Europe » that also tried but failed to block gay marriage in France, said Guillaume Bonnet, director of the Paris-based All Out equality group.

Most Slovak voters have shown no interest in the referendum, while nearly half of those offering an opinion say they favour legalising same-sex unions.

However the opinion polls suggest that only a third of eligible voters will turn up at the ballot box on Saturday, well short of the 50 percent threshold required for the referendum to be valid.

Last month, Slovak SRo public radio pulled an episode of a regular religious programme that included hate speech against sexual minorities.

A transcript of the unaired sermon by a Greek Catholic priest slanders gays as « filth » and a « plague » that must be driven out of Slovakia.

– ‘Where’s the mother’ –

Voting in the gay marriage referendum will start Saturday at 0600 GMT and finish at 2100 GMT. There are nearly 5,000 polling stations to serve around 4.4 million eligible voters. The results are expected late Saturday.

The vote will also focus on adoption rights for same-sex couples and whether sex education and lessons on euthanasia should be made compulsory at school.

One of several controversial videos posted on YouTube by gay marriage opponents shows an orphan asking « Where’s the mother » when he discovers that his adoptive parents are both male.

Opponents of gay marriage deny having a homophobic agenda.

« The referendum isn’t against same-sex couples, it’s for children, » Anton Chromik, spokesman for the Alliance For Family (AZR) that spearheaded the referendum, told AFP.

« Same-sex couples have the right to privacy, to freedom, » he said, but « children deserve both a mother and a father ».

« The European Parliament and some EU member states have passed laws that undermine the unique nature of marriage, families and children’s rights. We’re worried about parents losing the freedom to raise their kids according to their beliefs. »

EU rules allow each of the bloc’s 28 members to make their own decisions on issues like marriage and adoption.

A 2012 opinion poll in Slovakia showed that 47 percent of respondents supported civil unions for gays. Thirty-eight percent were opposed in the country of 5.4 million people, where 69 percent identified themselves as Roman Catholic in a 2011 census.

– Fear of diversity –

The Slovak ban on gay marriage contrasts sharply with its legalisation in more than a dozen countries, including Argentina, France and the United States.

Leftist Prime Minister Robert Fico sought to sway conservative voters in his failed presidential bid in 2014 by amending the constitution to define marriage as a union between man and woman, effectively banning same-sex marriage.

To ensure the ban would stick, the AZR went ahead and gathered the 400,000 signatures needed for the referendum.

For Bratislava art gallery owner Andrea Pallang, 40, who has been living with her girlfriend for eight years, the ban hits very close to home.

« I feel discriminated against in tax, social and healthcare policies, » Pallang told AFP, adding that « it’s as if we don’t exist. »

But the AZR has convinced 27-year-old tourist agent Eva Lajchova. The Bratislava resident says she backs the ban « because I care about the future of Slovakia and my future children. »

Marian Lesko, an analyst with the Bratislava-based Trend business weekly, explains the larger factors behind the prospect that the ban will remain intact for some time.

« Compared to neighbouring countries, Slovakia is quite conservative in respect to cultural-ethical issues due to strong religious beliefs, the country’s isolation during the communist-era and a fear of diversity, » he told AFP.